ISBN 5–94420-021-9

This brochure is about the Rodina electoral bloc in the 2003 Duma elections, the Rodina fraction in the Duma, and the party of the same name, created in 2004 and headed by Dmitri Rogozin.

The brochure gives an account of the emergence of Rodina and describes its constituent parts and internal conflicts as well as key events, in particular the split of the fraction, the story of the ‘Letter of the 500’, Rodina’s participation in regional electoral campaigns etc.

It includes biographies of the leaders of the fraction and party (Dmitri Rogozin, Sergei Glazyev, Andrei Saveliev, Natalia Narochnitskaia).

This brochure will be of interest to political scientists, journalists and historians, as well as to all those interested in contemporary Russian politics.

Published with the support of the Henry M. Jackson Foundation.

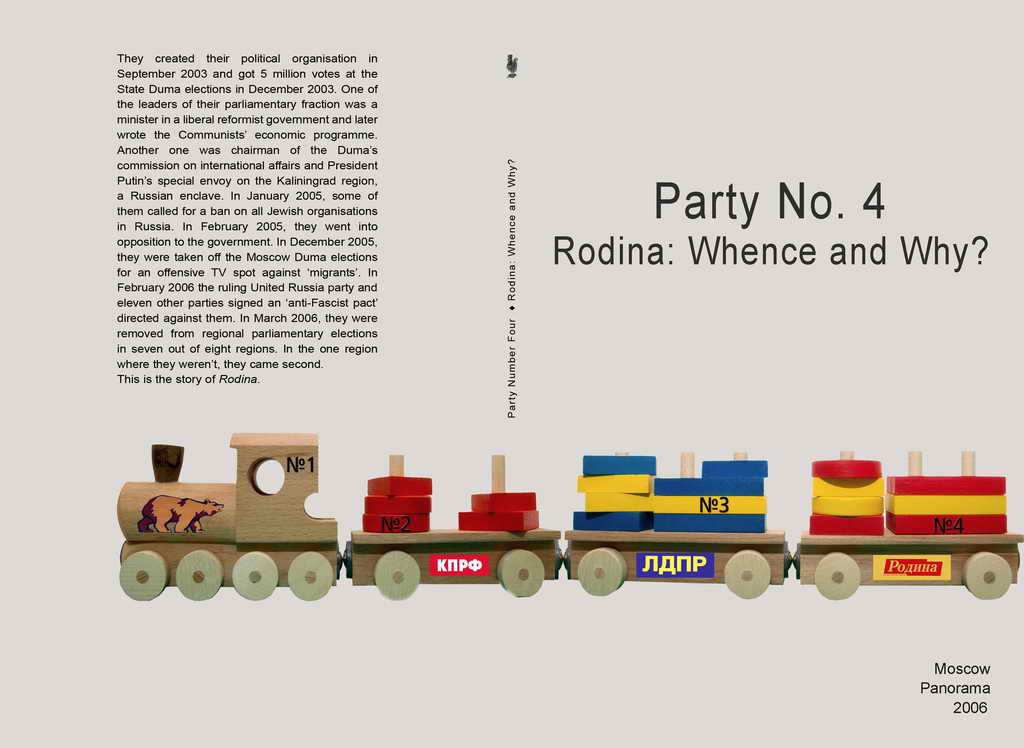

Cover design: Alexander Petrushin.

The cover illustration includes pictures of a wooden educational toy produced by Fabrika igrushek Ltd – http://vozik.ru.

You are free to reproduce the entire text of this book or any part thereof as long as you properly attribute it.

Web site: http://orodine.ru

Panorama Centre, 2006

Contents

Foreword........................................................ 4

What is Rodina.................................................. 6

The Nine Faces of Rodina ................................... 6

2003. The Construction and Launch of the Rodina Comet.......... 11

2004. The Presidential Election and the First Split............ 18

The ‘Year of Truth’ and its Consequences....................... 20

Rodina at the regional elections .......................... 29

Is it true that Rodina......................................... 30

The ‘Oligarchs’............................................ 30

‘A Kremlin Party’.......................................... 33

‘Nationalists’............................................. 35

Scenes from the Life of Rodina................................. 39

The ‘Letter of the 500’.................................... 39

The ‘Let Us Purge Moscow!’ TV spot ........................ 42

Rodina’s bills ............................................ 47

Dramatis personæ............................................... 49

The electoral list ........................................ 49

Dmitri Olegovich Rogozin .................................. 49

Sergei Yurievich Glazyev .................................. 54

Andrei Nikolaevich Saveliev ............................... 58

Alexander Mikhailovich Babakov ............................ 61

Natalia Alekseevna Narochnitskaia ......................... 62

Afterword...................................................... 64

Notes.......................................................... 67

Foreword

Rodina (an electoral bloc, a political party and a parliamentary fraction) has been the most interesting political project in Russia in 2003–2006. The dramatic twists in Rodina’s fate – its sudden initial ascent, the serious internal conflicts and tensions, the party’s attempt to play a political game of its own and the ensuing sanctions – highlight more general and deep-seated recent tendencies in Russian politics. The story of Rodina shows that nationalism goes down well with voters and that the Kremlin exercises full control over the party system.

The literature about Rodina, the bloc as well as the party, is scanty. Its early history (until the spring of 2004) is described in detail, though not impartially, in a book by Olga Sagareva, the bloc’s former press spokeswoman.1 The party’s ideological platform is analysed in an article by Marlène Laruelle.2 And that’s all – beyond this we’re left with press articles which are often interesting but do not provide a comprehensive idea of Rodina. This brochure is an attempt to fill that gap.

This study is based on data from publicly available sources, including press publications, transcripts of TV and radio appearances, official documents from the State Duma, electoral commissions, and the party/bloc itself. The personal impressions our correspondents gained at congresses, mass-meetings, pickets, meetings with voters and other events organised by Rodina activists are another important source. The biographies are based on material provided by Vladimir Pribylovsky, who kindly agreed to read the entire manuscript of the book.

We have greatly profited from data provided by the SOVA research centre, especially concerning the ‘Letter of the 500/5000’. We would also like to thank all participants of a round table discussion on the future of Rodina at the Panorama Centre on 2 February 2006: the opinions expressed during that discussion have informed the final stages of work on the brochure. Our colleagues at the Panorama Centre, especially Ilya Budraitskis and Yulia Smoliakova, have also made a substantial contribution. To all of them go our heartfelt thanks.

The main body of the text was finished in February 2006. Minor corrections were made until mid-March. The afterword was written on 26 March.

‘Party Number Four.’ Rodina: Whence and Why? is the final report on a research project ‘Rodina i okrestnosti’ (Rodina in context) carried out by Panorama in June 2005 – March 2006. The other data gathered during that project are presented online at http://orodine.ru. Readers looking for more detailed information about Rodina are invited to consult that web site.

Please e-mail your corrections, remarks and suggestions to info@panorama.ru.

Translator’s note: A somewhat inconsistent but readable ‘journalistic’ transliteration system has been used in the main body of the text to make it more accessible to non-specialist readers. Russian sources quoted in the footnotes and elsewhere are transliterated using a simplified version of the Library of Congress system.

What is Rodina

The Rodina (Motherland) bloc was the main political newcomer in Russia’s 2003 parliamentary elections: it garnered almost one-tenth of all votes cast and entered the State Duma along with three ‘old’ parties: United Russia (Yedinaia Rossiia), the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (Kommunisticheskaia partiya Rossiyskoy Federacii, CRPF) and the Liberal-Democratic Party of Russia (Liberalno-demokraticheskaia partiya Rossii, LDPR). The following year saw the creation of a party of the same name that continued the bloc’s political line. In contemporary Russian politics, few parties attract such perplexed interest.

Rodina is often mentioned to substantiate warnings about the threat of nationalism, xenophobia and a new redistribution of property in Russia. It is therefore important to understand whether Rodina represents a genuine danger, and, if it does, what the extent of that danger is. Political commentators are predicting that Russia will increasingly move towards a ‘few-party’ system dominated by one party, United Russia. This makes one wonder whether Rodina – an ambitious party which nevertheless has yet to grow if it wants to be a match for the top three – will be able to find a place for itself in the new political reality. Finally, more than any other party, Rodina warrants the puzzled question: what is it, and where does it come from?

It is not easy to find even a formal answer to that question. There is a steady stream of news about the Rodina party, the Rodina bloc, and other organisations bearing that name; these reports produce the impression that we are dealing with an unstable entity that is constantly at odds with itself and the surrounding world.

Anyone reading or writing about the variety of Rodinas must first pause to count its different – or identical – manifestations.

The Nine Faces of Rodina

1–2. The ‘Rodina (People’s Patriotic Union – Narodno-patriot-ichesky soyuz)’ electoral bloc in the State Duma elections in 2003. Its governing body is a supreme council elected at the bloc’s founding conference in September 2003. In 2003, the supreme council’s co-chairmen were Sergei Baburin, Sergei Glazyev, Dmitri Rogozin and Yuri Skokov. As of early 2006 there are two competing ‘supreme councils of the Rodina bloc’: one is chaired by Dmitri Rogozin and Sergei Glazyev, the other by Sergei Baburin (People’s Will, Narodnaia Volya) and Vasili Shestakov (Socialist United Party of Russia – Socialisticheskaia yedinaia partiya Rossii, SUPR).

3. The ‘Rodina (People’s Patriotic Union)’ fraction in the State Duma, co-chaired (since July 2005) by Dmitri Rogozin, Sergei Glazyev and Valentin Varennikov. As of February 2006 it consists of 29 deputies.

4. The ‘People’s Patriotic Union “Rodina” (People’s Will -SUPR)’ fraction in the State Duma. This was created in July 2005 and is chaired by Sergei Baburin. As of February 2006 it comprises 12 deputies.

5. The Rodina party (called Party of Russian Regions – Partiya Rossiiskikh regionov until February 2004) chaired by Dmitri Rogozin. Its executive committee is chaired by Alexander Babakov.

Logo of the Rodina

People’s Patriotic Alliance

|

6. The Rodina People’s Patriotic Alliance (Narodno-patrioticheskoe obyedinenie), created in 1998 under the name of Rodina Anti-Criminal Fellowship (Antikriminalnoe sodruzhestvo “Rodina”). This is an all-Russian social organisation that has a partnership with the Rodina party. Dmitri Rogozin is the chairman of the presidium, and Alexei Tikhonov, a member of the presidium of the Rodina party’s political council, is his deputy.

7. The Rodina People’s Patriotic Movement (Narodno-patrioticheskoe dvizhenie “Rodina”). This is a brand name registered in February 2004. The registration certificate no. 27359 is valid until December 2013; the owner of the brand is the Socialist United Party of Russia (SUPR). In early 2006 ownership of the ‘Rodina’ brand name was contested by representatives of the Rodina People’s Patriotic Alliance. In March 2006, their suit was dismissed by the Russian Patent Office’s Chamber of Patent Disputes.

8. The Rodina Coalition of People’s Patriotic Forces (Koaliciia narodno-patrioticheskikh sil “Rodina”). A group of politicians who, in November 2005, declared themselves the successors to the coalition of about thirty parties and social organisations who, in August 2003, had signed an Agreement on Co-operation between Peo-ple’s Patriotic Forces. The August 2003 coalition was a blueprint for the electoral bloc which, a month later, became the Rodina bloc. The leader of the new coalition is Nikolai Novichkov, who represented a little-known social organisation called ‘Dear Fatherland’ (Rodnoe otechestvo). In the list of signatories of the August 2003 agreement, Nikolai Novichkov’s name was somewhere in the middle.

9. The social organisation ‘Rodina People’s Patriotic Union’ (Obshchestvennaia organizaciia “Narodno-patriotichesky soyuz ‘Rodina’”). Created by Sergei Glazyev in January 2004; in April 2004 it was renamed For a Decent Life (Za dostoynuyu zhizn). Sergei Glazyev explained that the name of the organisation might be changed again in the future. Thus it might well become Rodina once again, and would of course be the actual, most genuine Rodina, just like all the others.

* * *

The politicians who are members of Rodina or one of its constituent parts, or close to it, seem to be doing all they can to confuse and distort the picture. Some of them invent new splits and coalitions where there is no-one who could split up or coalesce, then others make declarations about firm and unshakable unity where none is to be seen.

Leaving out trifles and details, there have only been two schisms and conflicts. The first of them, which took place in January-March 2004, divided Rodina members into supporters of Sergei Glazyev (who was then running in the presidential elections) and Dmitri Rogozin. Glazyev then – in March 2004 – declared that two Rodinas were about to emerge in the State Duma as a result of the conflict, and he could not stay in what he called the ‘Surkov-Rogozin’ fraction. 3 (Vladislav Surkov has been deputy head of the presidential administration since 1999, in charge of internal politics, current politics and relations with parties and Duma deputies.) Then it turned out that there would be no second fraction (it did eventually emerge, but for a different reason), and that Glazyev could and did stay, despite the fact that he was removed from the post of fraction chairman.

The second schism, which took place in June-July 2005, redrew the battle lines: instead of ‘Rogozin and Baburin against Glazyev’, it was now ‘Rogozin and Glazyev against Baburin’. A new fraction called ‘Rodina (“People’s Will – Socialist United Party of Russia”)’ broke away and began to steer its own course; Glazyev became co-chairman of the Rodina fraction and now makes declarations in unison with Rogozin about the firm unity of the remaining deputies. True, at the beginning of 2004 Glazyev had also declared: ‘there are no problems at all, we have come to an agreement’ and ‘there is no doubt that we are together, that we have a single movement, a single fraction, a single cause’, but at the time Rogozin disagreed with him.

It has not been a rare occurrence in the history of Rodina for former allies who had split up, recently or a long time ago, to reunite. Thus when the bloc was founded in 2003, it brought together Dmitri Rogozin and Yuri Skokov, who had worked together in the mid–1990s in the Congress of Russian Communities (Kongress russkikh obshchin; Skokov spearheaded the CRC’s list in the 1995 Duma elections, and Rogozin was number 5) but had seemed to have severed their relations after a struggle for control over the CRC in 1996–97 and the ensuing partitions.

Alexander Prokhanov, the editor of the Zavtra newspaper, who is close to Rodina, in an interview likened this party to a ‘comet that attracts the painter’. 4 Rodina does indeed resemble a comet in some ways – its structure is just as complex, inchoate and unstable.

Dmitri Rogozin

|

During its flight, a comet sheds some of its parts because they have become useless, others break off on their own, and others still are drawn into its orbit. Among the objects revolving around the comet there are unidentified and artificial ones – such as the Coalition of People’s Patriotic Forces after its revival in the autumn of 2005. Dmitri Rogozin, the chairman of the Rodina party, is at no loss for expressive terms to describe these objects: sometimes he calls them ‘strange little hamsters’, 5 and sometimes ‘fattened polecats’. 6 Once his allies have ceased being allies, he also starts heartily calling them names. Baburin’s fraction to him is a ‘mole on United Russia’s backside’. 7 Glazyev and his allies, who in early 2004 announced the creation of the Rodina social organisation, were immediately dubbed ‘mice’ who will play while ‘the cat’s away’ (the cat, Rogozin, was then attending yet another session of the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly in Strasbourg). 8 Such language is typical of Rodina. Rogozin’s overly vivid and excessively figurative expressions have long been his distinguishing feature, adding to his fame as well as to his troubles.

2003. The Construction and Launch of the Rodina Comet

Rodina’s stylised red flag made its appearance in September 2003, when three parties – the Party of Russian regions, People’s Will and the Socialist United Party of Russia – officially formed a bloc to take part in December’s Duma elections. However, there is a story, or rather several stories, leading up to that event.

The most widely known and debated part of that story concerns Sergei Glazyev – a politician who had been minister for external economic relations, advisor to General Alexander Lebed, author of the Communist Party’s economic programme, and chairman of the Duma’s commission on economic policy. By early 2003 Glazyev had returned to being an ordinary Duma member, though he still had the reputation of being the most competent and promising economist among the ‘people’s patriotic’ opposition. Glazyev was then still a member of the CPRF fraction in the Duma, but the rumours that he would run for election independently, leading a bloc of his own, were sounding more and more plausible from the spring of 2003.

Throughout the spring and summer of 2003, Glazyev was declaring his intention to assemble the Communists, the Agrarians and their numerous (at least on paper) junior partners in the People’s Patriotic Union of Russia (a large and entirely decorative umbrella for organisations controlled by the Communist Party or prepared to collaborate with it that has existed since August 1996), but the likelihood of such a bloc coming into being was rather small from the outset. May 2003 saw the creation of the Comrade (Tovarishch) information agency, intended as a mouthpiece for Glazyev’s election campaign; it was energetic, aggressive and designed in the style of the 1920s Soviet avant-garde. It was the work of the gallery owner and ‘political technologist’ Marat Guelman, who was then the spin-doctor for Glazyev’s bloc. The bloc was then supposed also to be called Comrade.

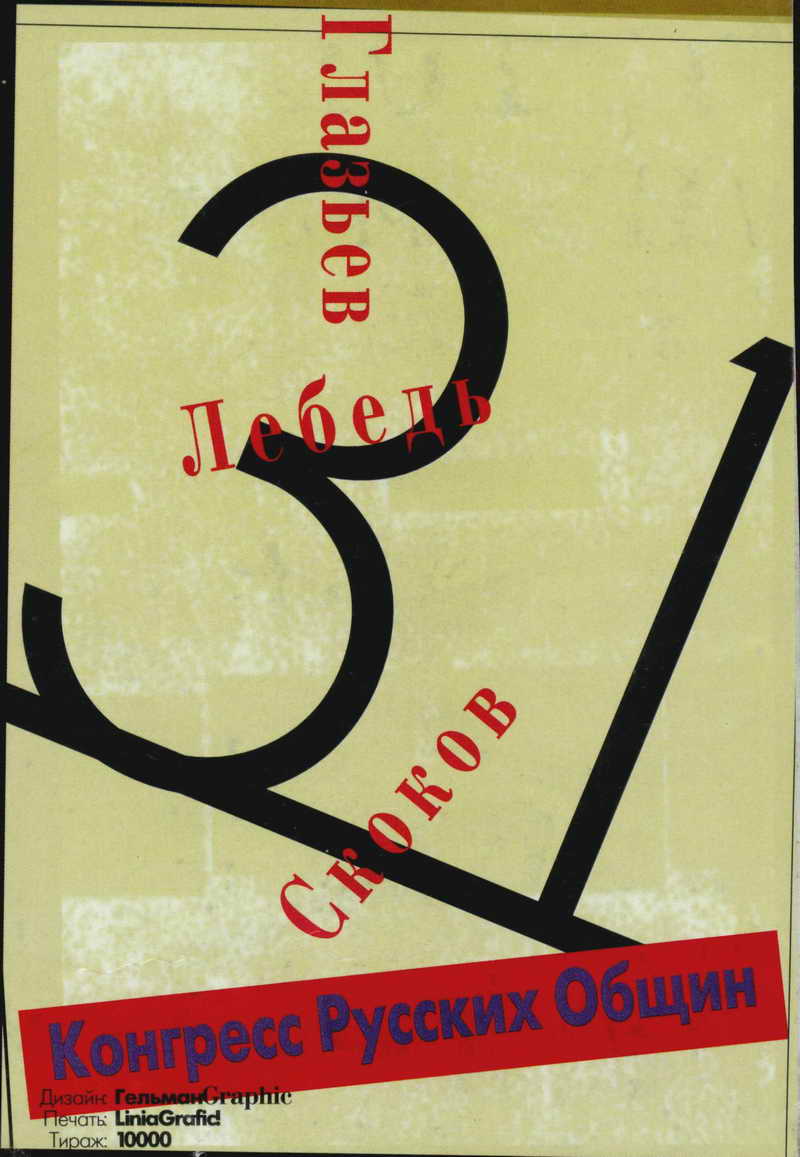

Congress of Russian Communities. 1995 election sticker (by the ‘Guelman Graphic’ Design Bureau)

|

In August 2003, ‘Glazyev’s bloc’ did at last make its appearance during an exhibition-cum-forum of political parties organised by the Central Electoral Commission in Moscow’s Manege. About thirty representatives of parties and social organisations – mostly little-known – signed an Agreement on Co-operation between People’s Patriotic Forces. Glazyev was the first signatory. The second name on the list was Yuri Skokov, formerly secretary of Russia’s Security Council, then chairman of the Russian Federation of Commodity Producers.

Sergei Glazyev, leader of the Party of Russian Regions (calendar, summer of 2003)

|

At the 1995 State Duma elections, Skokov and Glazyev were among the three top candidates of the Congress of Russian Communities, but since then Skokov appeared to have left politics. The Party of Russian Regions he founded in 1998 had until 2003 lived the inconspicuous life of a party that was left dormant to serve as material for future projects. Some of the component parts used to assemble the Party of Russian Regions had evidently been taken from store-rooms of 1995, for example the party’s newspaper, Voice of the Regions, which had previously served the CRC’s election campaign. Incidentally, Marat Guelman had also taken part in the 1995 Duma campaign, delighting voters with multi-coloured stickers displaying straight, slanted, inverted etc ‘31’s’ (the CRC’s number on the ballots). Another remarkable participant of the CRC’s 1995 election campaign, Dmitri Rogozin, appeared in the role of director of the election campaign headquarters of Glazyev’s bloc, having left Gennady Raikov’s People’s Party (Narodnaia partiya).

The respective roles of Yuri Skokov and Sergei Glazyev, who in June 2003 had become co-chairman of the Party of Russian Regions, were predictable: they were virtually the same as in the CRC eight years earlier. Skokov was the main mover and organiser; Glazyev was the face that attracted voters. By August 2003, several other celebrities had joined the bloc: the retired commander-in-chief of the Air Force, Georgi Shpak, former Central Bank chief Viktor Gerashchenko, and, somewhat later, the former commander-in-chief of the USSR’s land forces, Valentin Varennikov, ‘standard-bearer of Victory’ and Hero of the Soviet Union.

In early autumn, a new component joined the bloc: Sergei Baburin’s People’s Will party, which had previously intended to stand for the elections as part of an entirely different coalition, one that would have included a range of radical nationalist groups: the Russian National Party (Russkaia natsionalnaia partiya), the Slavic Party (Slavyanskaia partiya), Pamiat [Memory], the National Conservative Party etc, who had signed a declaration on the creation of a Coalition of People’s Patriotic Forces as late as August 2003. With the advent of Rogozin and People’s Will, the bloc ceased to be unambiguously left-wing and socially-oriented, starting to display a strong nationalist tint. Also at the turn of summer to autumn 2003, Oleg Shein’s moderate-left Russian Party of Labour (Rossiiskaia partiya truda) and Vyacheslav Igrunov’s Union of People for Education and Science (Soiuz liudei za obrazovanie i nauku, SLON) left the bloc. Marat Guelman suddenly disappeared, taking the Comrade trademark with him. In September, Glazyev dryly remarked that Guelman had ‘very actively offered the bloc his services, but they will hardly be required’.

‘Russian Party of Labour. No to the baseness in the housing and communal services!’ Drawing for a calendar for 2003

|

From the reminiscences of Duma deputy Andrei Saveliev, a long-standing companion-in-arms of Dmitri Rogozin’s (since the early 1990s):

‘The bloc’s troubles started immediately. In executing the task set by Voloshin [Alexander Voloshin, head of the presidential administration from 1999 to October 2003], Glazyev was prepared to rely on the shameless avant-garde political technologist, and deputy director of the First Channel, Marat Guelman, and run in the elections under that scandalising parody of a name, Comrade. This scenario was confounded by three factors: the consistent and subtle actions of Dmitri Rogozin, who gradually turned the bloc from a leftist to a national-patriotic one; the presence of Sergei Baburin, who at the last moment entered the bloc with his not-at-all-left-wing People’s Will party; and my modest efforts – above all a constant display of disgust for the ‘comrades’. 9

The national-patriotic turn of the bloc – which now changed its name to Rodina – in September turned out to have been even too drastic. At the end of September, Rodina urgently (after a phone call from the presidential administration, many commentators assure) had to purge its party ticket of activists of the Saviour (Spas) and Russian Rebirth (Russkoe vozrozhdenie) movements (closely linked to the Russian National Unity (Russkoe natsionalnoe yedinstvo) or RNU) who had entered it on People’s Will’s quota. Average citizens associated the RNU with black uniforms, a Nazi-like greeting and its emblem – an ornamented solar symbol reminiscent of a swastika. Spas and Russian Rebirth had kept that emblem.

Against the noisy backdrop of the investigation into the Yukos affair, which started around the same time, in September-August 2003, the Rodina bloc announced the main theme of its campaign: a struggle against the ‘oligarchs’ (big businessmen). Glazyev mostly spoke about the need to take the huge natural resource rent profits away from the ‘oligarchs’. Rogozin was mainly talking about the ‘oligarchs’ rebellion’. However, they were supplementing rather than contradicting each other.

In one of Rodina’s electoral TV spots, Glazyev and Rogozin are peacefully conversing over beer and dried fish in a cheap snack-bar:

These oligarchs, I don’t like them…

Serioga, you don’t like them, you don’t eat them!

In December 2003, the Komsomolskaia pravda newspaper thus quoted Rogozin’s declaration of his action programme: ‘First we need to destroy the oligarchs. This doesn’t mean they will physically disappear; it means there won’t be oligarchy, that is power won’t be in the hands of a few. Power shall be in the hands of the many…

We must start with Chubais. That has already been decided upon.’ 10 Judging from other renderings, Rogozin probably didn’t openly speak of ‘destroying’ anyone, but used more evasive phrases, such as ‘now there will no longer be an opportunity for there to be oligarchs’. Caution in his statements of ambiguous ideas and slogans is another of Dmitri Rogozin’s characteristic traits. While he shows little circumspection in his diatribes against political opponents, he strives to be as careful as possible in what he chooses to say or leave unsaid whenever he feels that a slightly greater liberty in his expressions might lead to accusations of, for example, inciting interethnic strife.

Later, in the summer of 2005, before the wave of accusations of anti-Semitism against Rodina had abated, Dmitri Rogozin confidently assured voters present at a meeting in the Moscow region that they were unfounded: ‘Yes, we do speak about oligarchs, but after all we don’t mention their names: Abramovich, Vekselberg, Fridman…’ There was an approving buzz in the audience, who obviously wasn’t overfond of ‘oligarchs’ with Jewish surnames. 11

Similarly, in their public pronouncements Rodina and its leader don’t speak out against ‘Caucasians’ ‘swarming’ into Russian cities: they are only concerned about ‘illegal migrants’ and, whenever necessary, ‘ethnic criminal groups’.

From an interview with Rogozin in the Nezavisimaia gazeta newspaper in November 2005, while Rodina’s campaign against ‘migrants’ was in full swing:

-Don’t you think nationalist groups will perceive your words as an appeal for action?

-But I don’t name any ethnic groups. I just indicate a certain direction. 12

Back in 2003 Rodina’s agenda and rhetoric garnered support. The bloc received nine per cent of votes in the election, which was universally acknowledged as a big and unexpected achievement. The bloc had been expected to get about half of that; it had been unclear whether it would enter the Duma. Both its supporters and its opponents agree that Rodina was one of the winners of the 2003 election.

2004. The Presidential Election and the First Split

The Rodina bloc’s success in the 2003 election made people wonder whether its first accomplishment would also turn out to have been its last, or Rodina would continue to develop. Sceptics usually named two reasons for not believing in Rodina’s future. Firstly, Rodina’s strong showing in the December election was largely due to television, where Glazyev and Rogozin were granted an enviable amount of airtime during their campaign. What would happen once TV support would end? Secondly, the politicians and parties gathered in the bloc were too diverse and too ambitious to get along together for any amount of time. At their first quarrel, Rodina would disappear.

There very soon arose an opportunity to test Rodina’s cohesion and the sceptics’ perspicacity. The campaign for the presidential elections started directly after the Duma campaign ended in December 2003. Glazyev, who had spearheaded Rodina’s party list, had never concealed his intention to move on and stand for president. It would have been practically impossible for him to win the elections; Vladimir Putin was obviously stronger. However, under favourable conditions, Glazyev could expect to come second, garnering about 15–20% of the votes. This would have confirmed him as the new, unchallenged leader of the left-wing opposition, giving him a good start for the 2008 presidential elections.

It didn’t work out. The powers-that-be had needed Glazyev for the Duma elections in order to weaken the Communists. In the presidential elections, Glazyev turned from an ally to a rival; thus there was no reason to help him, and so the help stopped. His biggest challenge, however, Glazyev was facing inside the Rodina bloc, among his recent comrades-in-arms.

At the very end of 2003, the bloc’s supreme council decided to nominate the retired chairman of the Central Bank, Viktor Gerashchenko, rather than Glazyev, as its candidate. Glazyev announced he would nominate himself, and it remained unclear whether Rodina’s supreme council had decided to support him as well as Gerashchenko or to deny him its support. Glazyev and Rogozin made conflicting pronouncements on this, and ordinary voters had practically no way of finding out who was right.

In January 2004, Gerashchenko was denied registration as a candidate by the Central Electoral Commission (CEC). It had turned out he had only been nominated by the Party of Russian Regions, rather than the Rodina bloc as a whole, which, according to the CEC, meant that he had to collect additional supporters’ signatures. Instead of doing that, he withdrew from the presidential race (with unconcealed relief, it seemed to external observers) and soon left politics altogether, becoming chairman of the board of directors of Yukos oil company.

Glazyev, who was now the only candidate from Rodina, tried to consolidate his position as Rodina’s number one, but met with stiff resistance.

In late January 2004, Glazyev convened a congress of the social organisation ‘Rodina People’s Patriotic Union’, which was intended to succeed to the Rodina bloc. However, this was not recognised as legitimate by Dmitri Rogozin and his allies. In February 2004, Glazyev attempted to secure the support of the parties which had created the Rodina bloc, but met with little success. He only enlisted the – wavering – support of People’s Will. The SUPR split into supporters of Sergei Glazyev and Vladimir Putin, respectively. Each of the two groups held its own party congress. In the end, the ‘Putinist’ SUPR, led by Vasili Shestakov from Saint-Petersburg, known as Pu-tin’s former Judo sparring partner, retained the party’s brand name. Glazyev was excluded from the Party of Russian Regions, and the congress of the party decided to rename it Rodina and declare its support for Putin in the elections.

In Rodina’s Duma fraction, an unstable balance had been preserved between Glazyev’s and Rogozin’s supporters. In March, the latter finally managed to gain a majority and ousted Sergei Glazyev from the leadership of the fraction, replacing him with Rogozin. Glazyev was much less successful in the presidential elections than he had wanted (2.8 million votes, or 4.1%), and lost more than he gained inside the Rodina bloc and fraction.

This course of events was one of the worst possible scenarios for Glazyev and Rodina: there had been an open conflict within the bloc, and in the presidential elections Rodina’s candidate achieved a worse result than the Communist Party’s nominee. Nevertheless, these results were ‘almost satisfactory’ rather than ‘poor’. For Glazyev, almost five per cent in the presidential elections was enough to keep his place as a powerful and significant politician. The fraction formally remained united, which made it easier for Rogozin and Glazyev to form an alliance in 2005.

Another outcome of the 2004 crisis was the emergence of a party called Rodina, and thus of the perspective that what would stand in the next elections – under the same name and with a similar programme – would no longer be a loose bloc, but a more organised political entity (in 2005, yet another change in electoral legislation excluded blocs, rather than parties, from running in elections altogether).

Back then, in early 2004, the prospects of the new party looked extremely uncertain. It was not known whether voters who had supported the ‘Glazyev bloc’ in the Duma elections would vote for ‘Rogozin’s party’. The Rodina party stood little chance of reuniting all the main participants of the 2003 bloc. However, the 2004–5 regional elections proved that a party led by Rogozin will get about the same amount of support as the Rodina bloc did in 2003. Uniting the former allies proved more difficult: neither People’s Will nor the SUPR could be persuaded to join.

The ‘Year of Truth’ and its Consequences

2005 was a special year for Rodina, both as party and as a fraction. Towards the end of the year, the party’s chairman Dmitri Rogozin called it a ‘year of truth’ during which Rodina proved itself as ‘the only true opposition force’ and ‘only grew stronger’ despite all attempts to ‘discredit and smash’ the party. Politicians are prone to exaggerations, but it is certainly true that Rodina in its present state can only be understood if we take into account its experience in 2005, when it tried to present itself to voters as a truly oppositional force rather than a reserve presidential ‘left-hand party’ (to use a phrase common in Yeltsin’s times).

Even the party’s colours changed: from red to red-and-yellow. ‘If red is the colour of sunset, then yellow is more associated with dawn’, the fraction’s press service explained. 13

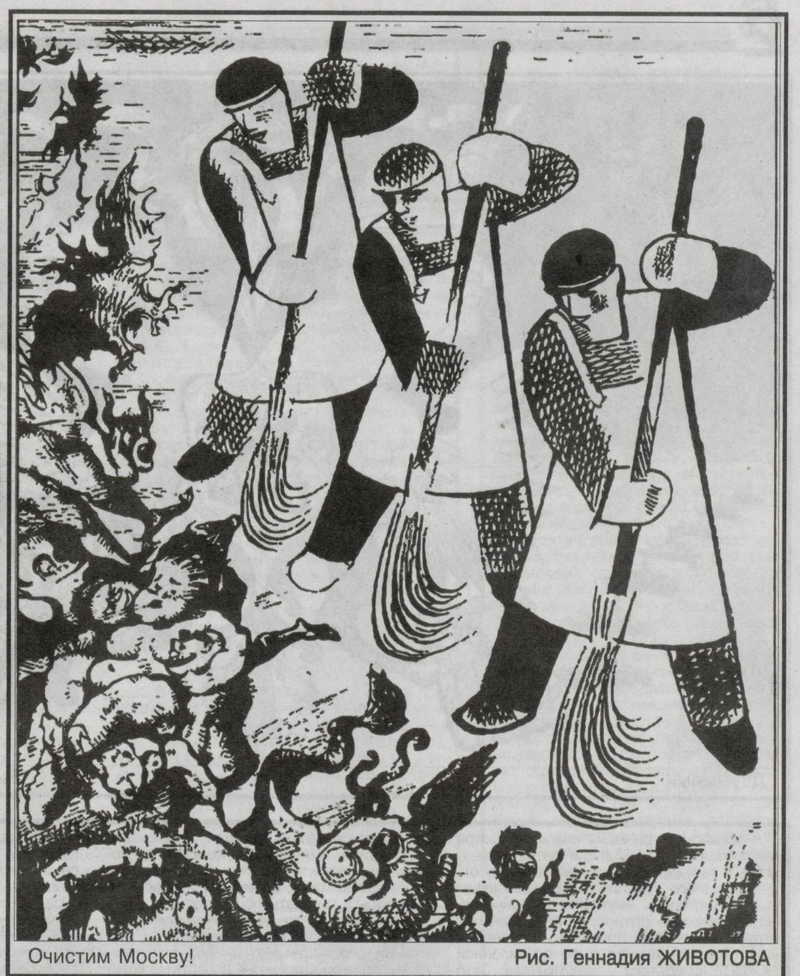

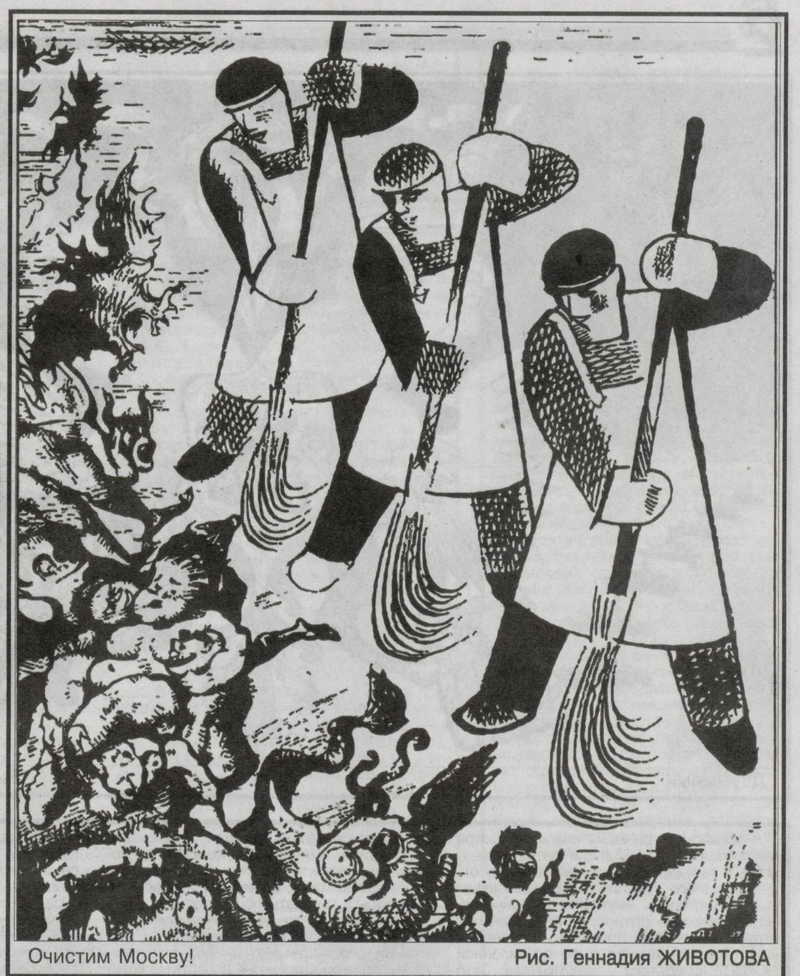

‘This is how we’ll win!’, a drawing by Gennady Zhivotov in Zavtra.

Illustrations to Dmitri Rogozin’s programmatic text ‘Economic War’.

The people depicted are (from left to right)

Eduard Limonov, Gennady Ziuganov and Dmitri Rogozin

|

This project didn’t get very far: the Central Electoral Commission ruled that most of the questions proposed violated referendum legislation. According to Russian law, no referendum may be held without the approval of the electoral commission. Later, in summer-autumn 2005, the Communist Party held a poll where the questions from the abortive referendum were put to its supporters in a so-called ‘people’s referendum’.

The year began with a governmental reform which replaced noncash social benefits with cash payments (‘monetisation’) and whose first result was a wave of protests, especially among pensioners in big cities (Rodina’s main supporters in the 2003 elections). The government had a hard time of it, but the parties, in a way, fared no better: they needed to stand out among the general chorus of critics and find something special that voters would remember them by. Rodina needed at least to keep up with United Russia and appear just that one step more determined. It seemed to have found a way of doing so. Five deputies from the Rodina fraction, including Dmitri Rogozin himself and his long-standing faithful ally Andrei Saveliev, went on a hunger strike. This was much talked about, as was Rogozin’s statement in February 2005 after interrupting the strike: ‘We are no longer the president’s special task force’. 14 Also in early 2005, co-operation between Dmitri Rogozin and Sergei Glazyev resumed. Glazyev proposed to hold a referendum on approximately fifteen issues, mainly relating to social policy.

Rogozin characterised the ‘party of power’ in an electoral TV spot in February 2005 in his home region of Voronezh (Rogozin is the Duma deputy for the Anninsky electoral district there), where he ran in the regional elections as number one (or ‘steam engine’, a recognisable figure helping to win votes for his party but not intending to take up a parliamentary seat) on Rodina’s party list. Since then Rogozin has regularly been summoned to courts or to the Duma’s ethics commission by offended members of United Russia.

By the middle of the year, Rodina’s rhetoric became distinctly more inflammatory than before. Rogozin’s speech at the party’s June 2005 congress was true to the party’s new style. It ended thus:

‘Long live the social, anti-criminal, anti-oligarchic, anti-corruption and scientific-technical revolution! (Applause.) Down with the horrors of corruption! Long live the Rodina party – the avantgarde of the movement of resistance against the anti-social, anti-people course! The dragon shall be killed! Victory will be ours! Glory to Russia! (Wild applause.)’ 15

Rogozin threatened the government with mass protests in case the authorities decided (just let them try!) to miscount the results of the 2007 Duma elections.

‘Then there will be not thousands, but hundreds of thousands of us, and if the authorities decide to hinder us, their water-jets will choke on their own water. If they use force against us, then those who do this will choke on their own blood.’ 16 This is what Rogozin, to the roar of the loudspeakers, promised about 1,000 supporters at a mass-meeting that took place immediately after the congress, in June 2005. There were few sympathising ‘men of the street’ or simply curious passers-by. The main body of the audience was composed of party activists who had been assigned places in advance and were holding identical yellow-and-red party flags that came from one lorry. Somewhat earlier, at the party congress, those same party activists had, in an industrious display of solidarity, supported all of the party leadership’s nominees for Rodina’s political council. Six hundred delegates voted ‘in favour’, and one or two ‘against’. At that time, in mid-September 2005, Rodina particularly resembled a machine – one that hasn’t been fully assembled yet but is already prepared to gather speed given a little extra fuel and an absence of disturbances.

But disturbances were to come, and soon. The party’s June meeting in Moscow did not turn out as the party had wanted: the planned procession through one of the central streets was banned by the city administration at the last minute. Also in June, Rodina was at last taken to task for an anti-Semitic letter to the Prosecutor-General’s Office sent in January 2005, signed by 13 deputies from Rodina’s Duma fraction and six Communist deputies. The scandal was trigered by an announcement made at Rodina’s congress that the party intended to apply for membership in the Socialist International. Two small socialist parties, the Social-Democratic Party of Russia and the Party of Social Justice, issued a statement to the effect that this respected international organisation must not admit populists and anti-Semites; after that the topic was taken up by the Jewish cultural communities, then by the newspapers, until at last almost everyone was talking about it.

As the controversy about the anti-Semites in Rodina was still raging, the Rodina fraction in the State Duma split, this time into Rodina and People’s Will deputies: respectively, supporters of Dmitri Rogozin and Sergei Baburin. Baburin, who had been expelled from the Duma fraction after making a number of harsh statements about Rodina (among other things, he accused the party of collaborating with the Communists, ‘oligarch’ Boris Berezovsky and the Ukrainian ‘orange revolutionaries’) in June 2005, took around ten People’s Will deputies with him. The management of the State Duma manifestly took Baburin’s side. The new fraction, called ‘Rodina (People’s Will – SUPR)’ was registered despite the fact that it included five times fewer deputies than are needed to form a deputies’ group according to the Duma’s regulations. Baburin kept the post of Duma vice chairman, to which he had been elected in 2004 on the Rodina fraction’s quota; thus Rogozin’s and Glazyev’s Rodina was left without a vice chairman position. ‘There was one bloc in the elections, so it is entitled to one vice chairman’s post,’ the regulations commission explained.

The elections to the Moscow City Duma were going to be the main test for the party in 2005. Rodina started preparing in good time. At the start of its campaign it duly declared that large-scale election-rigging was being prepared and that the party would of course do everything to prevent that. It held a debate – noisy enough to be noticed by all those who cared – on how exactly the party would protest against the (obviously!) incorrect results of the Moscow elections.

A foreign guest at Rodina’s congress in June 2005, a Finnish social-democrat, was so impressed by a mass-meeting the party held that he gave a speech to its participants, saying that what he saw in Moscow vividly reminded him of Kyiv half a year earlier – even the colour of the flags was the same. The crowd was buzzing with disapproval: the overwhelming majority of Rodina members consider the Ukrainian ‘orange revolutionaries’ their political opponents. The similarity of their tactics was, however, obvious and even provocative.

In September 2005, Sergei Shargunov, the leader of the Union of Youth ‘For the Motherland!’ (Soyuz molodezhi “Za Rodinu!”) warned: ‘If the elections are rigged, there won’t be a Maidan, but there might be a Manege’. (Apart from designating an exhibition hall next to Kremlin, ‘Manege’ is also a colloquial term for the adjacent Manege Square - Manezhnaya ploshchad, which was the scene of political mass meetings in the early 1990s.)

It was also in the run-up to the Moscow elections that Rodina finally provided itself with a party newspaper. Reading Zavtra, with its permanent editor-in-chief, the writer Alexander Prokhanov, its bombastic style and simple illustrations, had been a habit with nationalists of different hues – both ‘whites’ and ‘reds’.

For a long time, starting in the mid–1990s, the newspaper had supported Gennady Ziuganov’s Communist Party, but in 2005 it switched allegiance to Rodina and Dmitri Rogozin. It promised to be a mutually beneficial union: the paper got a guaranteed circle of subscribers and readers (the party’s one hundred thousand members), while the party got a recognisable brand name.

The ‘Pulse of Rodina’ rubric in Zavtra

|

The deal had been in the making since the summer, and was officially declared in November.

To make it more solemn, the announcement was timed to coincide with the one-hundredth anniversary of the publication of Lenin’s article ‘On party organisation and party literature’ (which had been compulsory reading for all schoolchildren and students in Soviet times).

At the press conference on the union between Rodina and Zavtra, Dmitri Rogozin explained that he especially liked the news-paper’s breadth and openness, its readiness to open its pages to a great variety of points of view, to work with a very broad circle of politicians and seek points of contact between them… At that very point, Sergei Baburin appeared in the Rodina fraction’s meeting hall with a group of followers – his office is still next door. Prokhanov immediately proved the breadth of his views by cordially embracing Baburin like a very good friend. Rogozin, who was sitting next to Prokhanov, quickly extended his hand to Baburin, awkwardly muttering: ‘Hello, Sergei Nikolaevich…’.

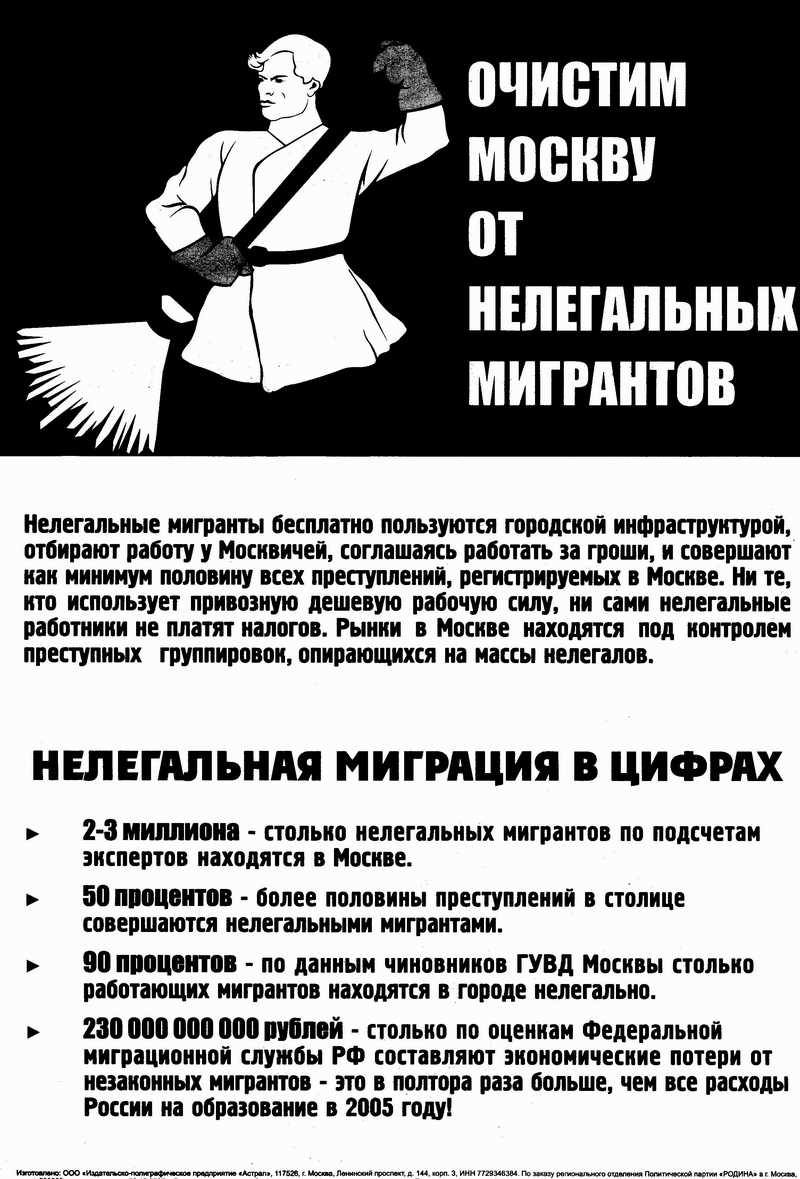

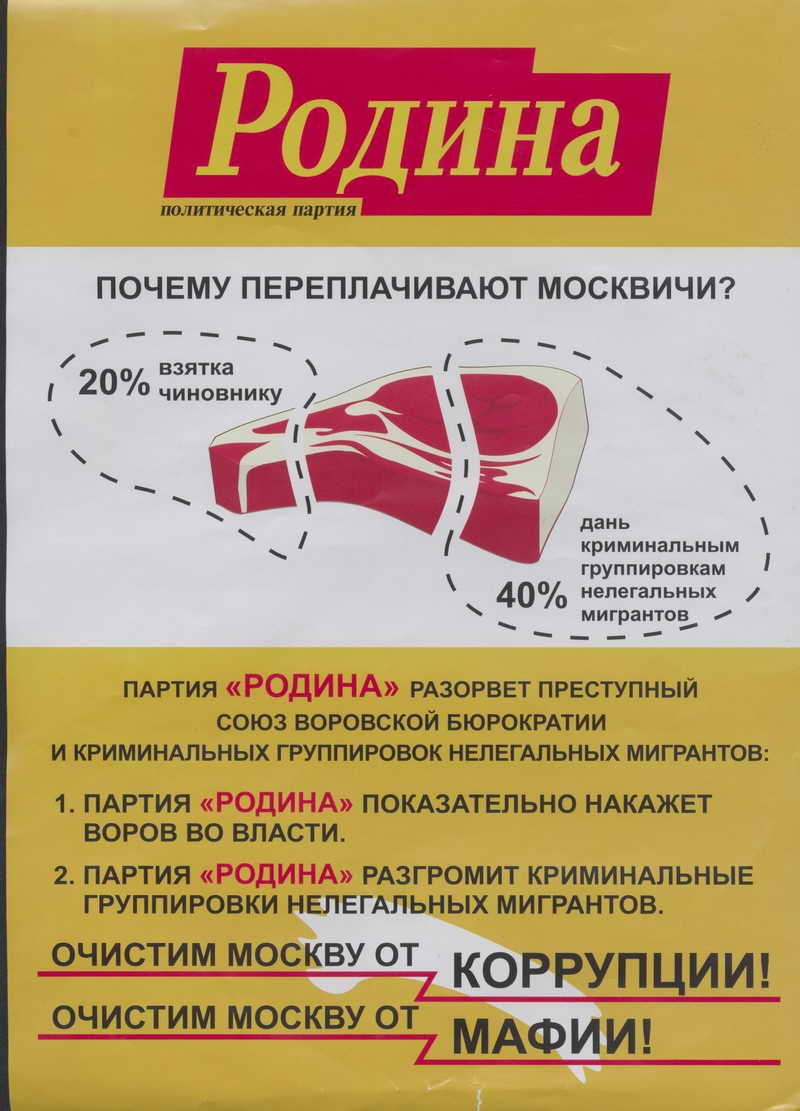

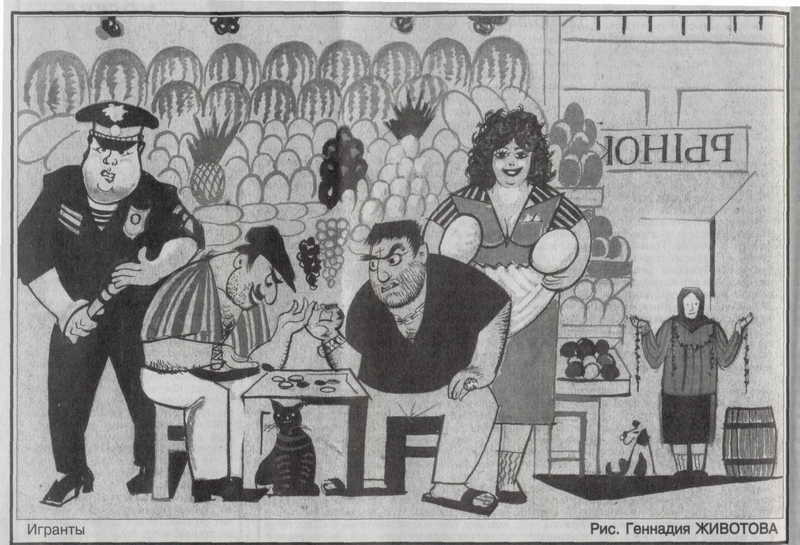

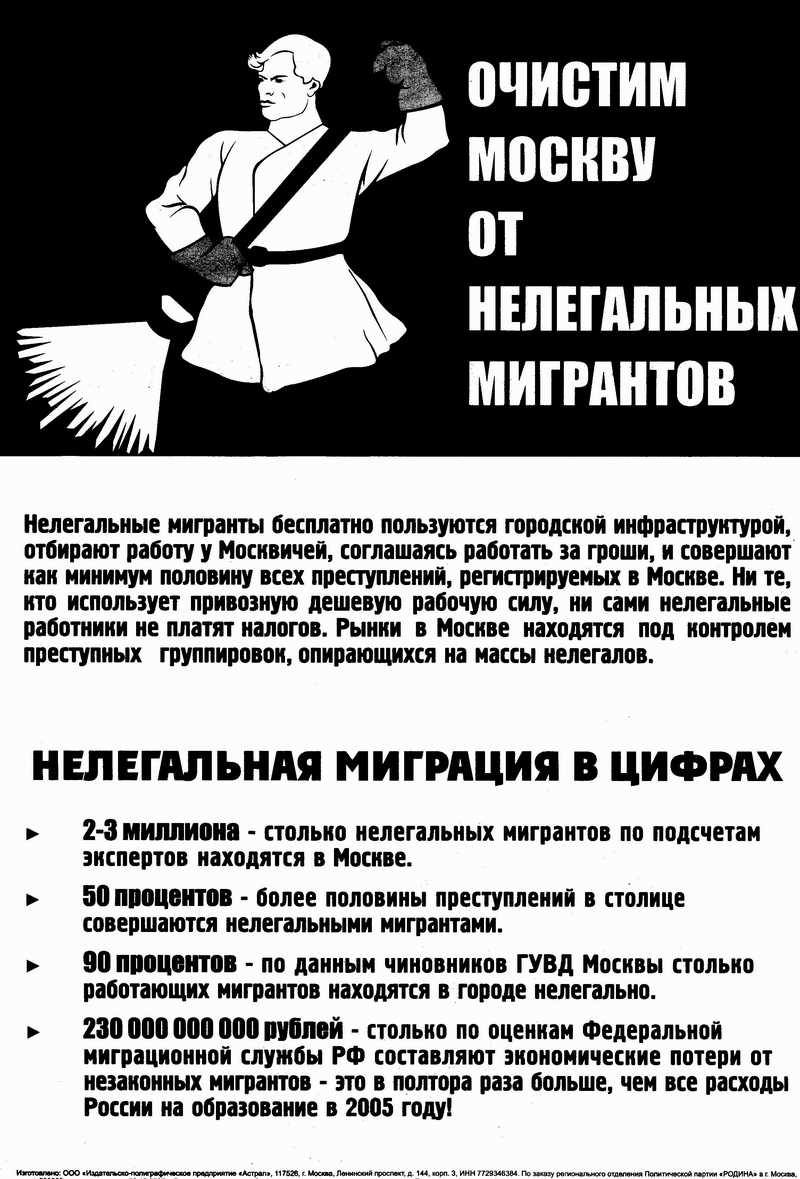

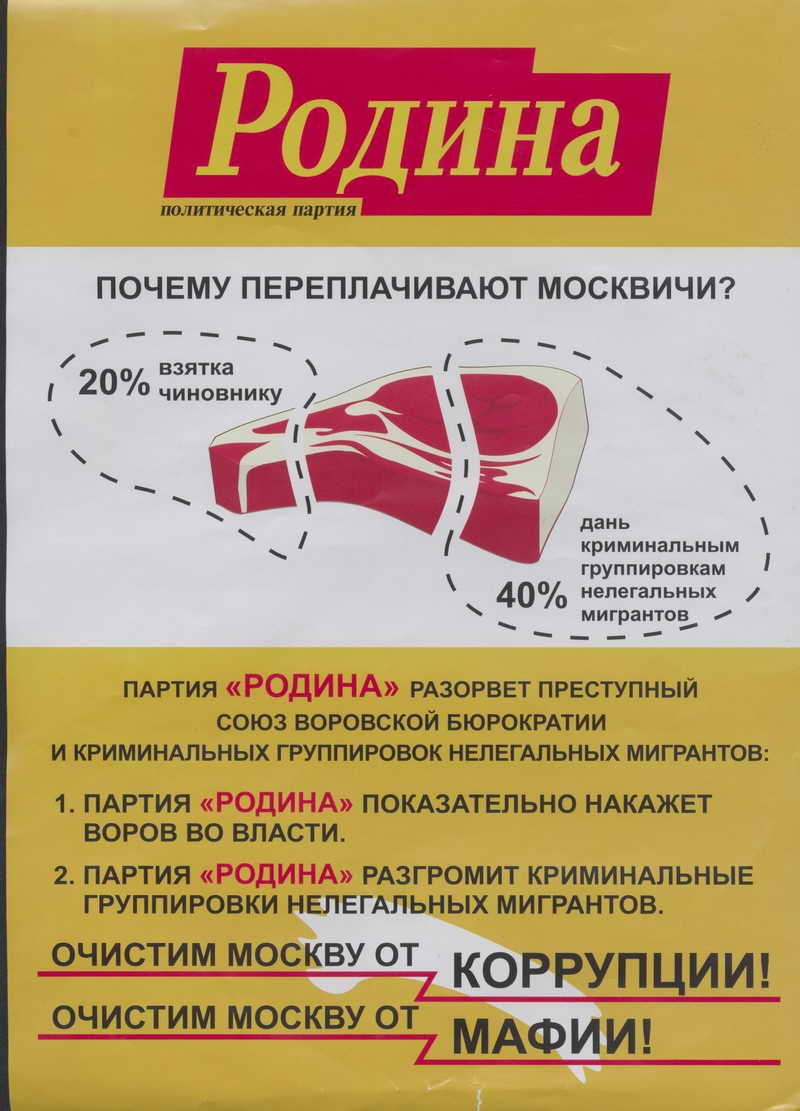

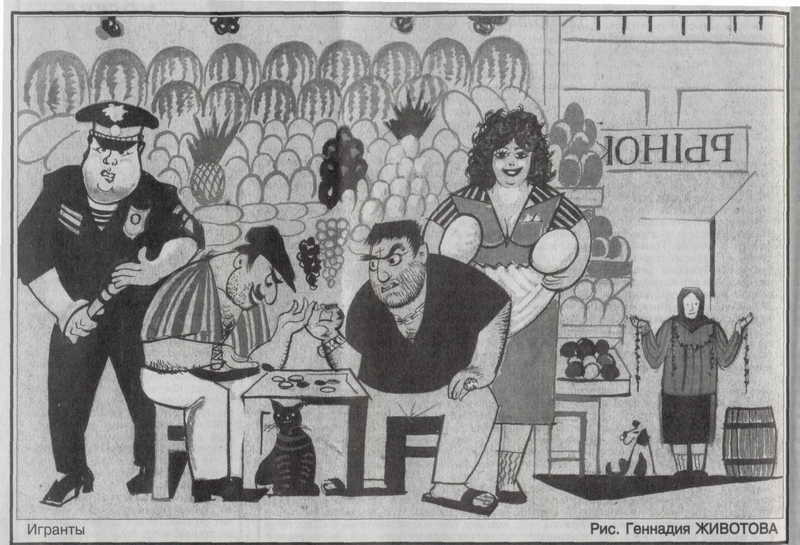

During the Moscow elections, the party chose ‘illegal migrants’ as its main enemies, followed by corrupt officials profiting from illegal migrants living in Moscow. The designation ‘illegal migrants’ was a thinly veiled expression of the average Muscovite’s hostility towards the Caucasians or Central Asians who come to Moscow to work on construction sites or as market traders. The depictions of ‘migrants’ in Rodina’s election newspapers faithfully reproduced the stereotypes about ‘Caucasians’: swarthy, unshaven, wearing large caps, standing behind counters with melons or watermelons. Rodina and its supporters were pictured as a man with a broom cleansing the city’s streets of ethnic crime and officials’ corruption. It is difficult to say how convincing this image was: most of Moscow’s street cleaners and refuse collectors are also migrants from CIS countries.

‘Let us purge Moscow!’ Drawing by Gennady Zhivotov in an election newspaper entitled ‘Moscow is our Motherland’ (published on 26 October 2005)

|

In Rodina’s electoral TV spot, this simple set of images and ideas was embodied in the slogan ‘Let us purge Moscow of rubbish!’ The spot did have the desired effect: Rodina was noticed, the party and its propaganda became the central topic of debate during the elections. But the price to be paid for this notoriety was exceedingly high: Rodina’s list was taken off the Moscow elections by a court decision. Ironically, Rodina was removed from the ballots following a legal suit filed by members of the LDPR, a party which used similar and even more outspoken slogans in its campaign (‘Close Moscow to Southerners’, ‘We are for a city with Russian faces. There is no place for illegals in the capital.’)

‘Why Muscovites overpay’ leaflet (published on 14 October 2005)

|

After Rodina was banned from the Moscow elections, it turned out the party had little to say for itself. In December, Rodina’s leadership declared that it renounced street protests; but all in all that step was forced upon it; there was nothing else it could do. Just like the LDPR, its neighbour in the political spectrum, Rodina is capable of attracting votes, but is not very good at bringing its supporters – simple sympathisers rather than professional activists – out into the streets.

Sergei Glazyev and Dmitri Rogozin at a press conference

|

After the Moscow elections, and especially from the beginning of 2006, Rodina changes again, once more becoming accommodating and constructive. The president designates four national projects as the year’s main tasks – Rodina adds two more: a project called ‘Preserving the Nation’ and a project to re-industrialise the country. The government starts a ‘gas war’ with Ukraine – Rogozin immediately suggests a way to reformulate Russia’s claims to Sevastopol in order to put pressure on the Ukrainian authorities. Russia is criticised for a new law that imposes severe restrictions on non-governmental organisations – Rogozin writes an open letter to foreign critics saying that judging Russian laws is none of their business.

Rodina members openly admit that they are now following the motto ‘Spare the party’ in order to let it survive until the next Duma elections in 2007 without taking too many blows. So far it is not entirely clear whether they will succeed. Rodina’s Duma fraction is shrinking: deputies are leaving it one or two at a time. The party is taken off the ballots in one regional election after the other. As a result, the party’s regional branches are becoming less and less attractive for ambitious local officials or businessmen who, until quite recently, saw Rodina as a relatively advantageous platform for their political careers. The party’s crisis has become obvious.

So far, Rodina’s leaders are cheering up their supporters with pugnacious statements.

Andrei Saveliev (February 2006):

‘In Moscow, by our calculations, our popularity rating is about 30%. In other regions, it is also rising. And the authorities won’t be able to do anything. They think that by repressing our organisation they will crush us completely. But if they don’t succeed we shall be their funeral team.’17

The (almost) party newspaper Zavtra is also trying to convince its readers that Rodina ‘is not hardened, cooling-down carrion, but a live, pulsating organism’.18 Opinion is divided on the extent to which this optimism is warranted. In any case, no matter how the story of Rodina will end, it is already quite instructive.

Rodina at the regional elections

Rodina constantly runs in elections for regional legislative assemblies, starting with the Irkutsk regional elections in October 2004. The party achieved its best regional result in the Voronezh region (21.0%), where Dmitri Rogozin spearheaded its electoral list. The party also did well in the Ryazan (13.0%), Arkhangelsk (12.7%), Kaluga (11.2%), Ivanovo (10.5%), Kostroma (9.1%), Tver (9.0%) and Khabarovsk (10.6%) regions and the Yamalo-Nenets autonomous district (11.3%). Almost everywhere it crossed the 5% threshold stipulated in most regions, with the exceptions of Chechnya and the Kurgan region (Rodina only got 4.0% in the Amur region, but the threshold there is 3%).

Rodina met with a serious rebuff in the regional elections of spring 2006. The party put forward a list of candidates in all of the eight contested regions, but eventually it was taken off the ballot in all but the Republic of Altai, where the party got 10.5% of the votes, coming second. The electoral commissions’ refusal to register Rodina (or the cancellation of the registration in court) was usually motivated by violations committed at the regional conferences that selected the candidates or related to the presentation of lists of signatures.

The 7% barrier which will be in force at the 2007 State Duma elections looks dangerously high for Rodina: its lists got less than 7% in every other election, including the Novosibirsk and Tambov regions, where a 7% threshold was already in effect at the December 2005 elections.

Is it true that Rodina…

Neither politicians nor commentators are left indifferent by Rodina. Much is being said about the party – bad things more often than good things. And Rodina does not listen silently. As is the convention in politics, parties need to be talked about; in a sense, parties are what is being said about them. External appraisals of the party by and large boil down to three judgments: (1) Rodina is only pretending to combat the ‘oligarchs’, while in actual fact it is serving those (or other, competing) oligarchs. (2) Rodina is not an independent party, but a Kremlin project. (3) Rodina is a party of nationalists and extremists, or, on more radical views, of ‘national-socialists’ and ‘fascists’. Let us try to examine these views in some detail.

The ‘Oligarchs’

The first judgment, the one about the ‘oligarchs’, is voiced less often than the others, and does not look very persuasive. During the 2003 Duma elections, the Rusal (Russky alyuminiy) company and its owner, Oleg Deripaska, were usually designated as Rodina’s source of funding. In November 2003, one of the leaders of the Union of Right Forces, Boris Nemtsov, during a televised debate with members of Rodina, claimed that ‘the Rodina bloc is financed by the aluminium oligarch Deripaska’. The Rodina politicians disagreed and demanded proof, threatening to sue Nemtsov. Neither the proof nor the legal suit ever materialised. It is perfectly possible that Deripaska did fund Rodina, but he is more likely to have done that by agreement with the Kremlin rather than heeding his soul’s call.

The other person ‘generally known as Rodina’s source of funding’ in 2003 was the president of the National Reserve Bank, Alexander Lebedev. This case is more clear-cut. Firstly, Lebedev was then on Rodina’s party electoral list (he was number one on the Moscow list) and was elected to the Duma on the party’s ticket: the connection is too obvious to be whispered about with the air of experts. Secondly, Lebedev just as openly left Rodina immediately after the 2003 elections and became a member of the United Russia fraction.

Around the middle of September 2005, Rodina’s opponents, especially from the ruling United Russia party, were trying hard to uncover Rodina’s links with Yukos and its former owner, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who had already been convicted in court. The evidence presented was very shaky (the director of United Russia’s executive committee, Andrei Vorobiev, stated that ‘Rogozin’s latest interviews give the impression that he and Khodorkovsky are companions-in-arms’), but the allegations were repeated with enviable regularity. They also mentioned the banker Viktor Gerashchenko, who had joined Yukos in early 2004, although it is clear that this was a ‘different’ Yukos, one that had been weakened beyond hope of recovery by the arrests of its co-owners and top managers.

Andrei Vorobiev (United Russia), ‘Open Questions to Dmitri Rogozin’: ‘So, I would like to know whether Rogozin knows how many supporters of Khodorkovsky there are among the members of his party and who they are; whether he himself shares Khodorkovsky’s views […] and, finally, whether Rogozin will tolerate Khodorkovsky sympathisers in his ranks, just as he tolerates anti-Semites?’ 19

Overall the attempts to prove that Rodina has excessively close ties with big business have hardly been successful. Especially since other critics assert the exact opposite: according to them Rodina has become so intemperate and extra-systemic that all its former partners from the business world have turned their back on it, ‘leaving the party with no-one but Klimentiev’.

Andrei Klimentiev, an infamous businessman from Nizhny Novgorod who has been convicted of several crimes, came to wide fame in the spring of 1998 after winning the Nizhny Novgorod mayoral election. Immediately after the election he was once more arrested, convicted and taken to a prison in the Kirov region. He is often mentioned to illustrate the thesis that criminals might come to power at a local and regional level. In December 2005, Klimentiev was unexpectedly put on Rodina’s list in the elections to the regional legislative assembly; in January 2006 he was arrested yet again.

Calmer analysts of Rodina’s sources of funding usually agree that large-scale financial support mainly comes from Alexander Babakov, who occupies the post of leader of the party’s executive committee.

Here is how Babakov himself relates the story of his business achievements:

‘I started my own business by working for the Voznesensky leather production and currying factory (the Vozko close corporation in the Mykolayiv region of Ukraine). This factory wasn’t a monopolist, but there were only few other companies on the market. At first I represented its interests in Russia, then I created a company that sold tannery products here and became its co-owner.

In the early 1990s, a company called Promsvyaz was created in Ukraine, which produced goods for the communications market – both metal constructions and electronics: computer programmes, phone cards. It was supplying 90% of its production to Ukrtelekom. I was a member of the board of directors of the company until I was elected to the State Duma.

I have also tried my hand at the service sector. At one point I got interested in the hotel and tourist business. I was also in charge of supplying Russian oil products to Ukraine. All in all, I have worked in multiple lines of business.’

Vedomosti, 26 July 2005

Most discussions of Babakov’s business career mention his supposed links with the so-called ‘Luzhniki group’ of criminals who in the 1990s controlled the clothes market in the Luzhniki stadium. Babakov confidently asserts that this is some mistake.

‘I don’t know what this [the ‘Luzhniki group’] is. My surname is different. I am not involved in any business linked to that name. This canard was probably launched on the Internet. There was a time when people used to link Moscow’s representatives to Luzhkov. We were sometimes called the Luzhkov people, maybe that’s a slip of the tongue.’20

‘A Kremlin Party’

It has never been seriously disputed that Rodina is a ‘Kremlin project’. On the contrary, for a long time Dmitri Rogozin preferred stressing his special relationship with the presidential administration, considering it one of his strengths. It was also Rogozin himself who described the party as ‘the president’s special task force’.

Olga Sagareva, former press secretary of the Rodina bloc in 2003:

‘[Rogozin, coming to the bloc’s electoral headquarters] greets us and immediately solemnly declares: “I recently spoke to the president, and the president once again confirmed that he considers this project his personal project.”’

It is easy to notice that even in his most daring speeches ‘against the authorities’ Dmitri Rogozin never, or only very softly, criticises Vladimir Putin.

Dmitri Rogozin in an interview to the Strana.ru web site (October 2005):

‘You know, the president’s speeches don’t contain a single word I would disagree with. The president says the right things, but for some reason they don’t get implemented. I don’t know that reason […]. But if he says those things sincerely, then we have a field for cooperation. We’re not a frenzied opposition after all.’

Disagreement focuses on the following, more complicated questions: which part of the presidential administration are (or were) Rodina and Dmitri Rogozin linked to, and have these connections remained intact after Rodina declared it was going into opposition?

There are at least two accounts of Rogozin’s relationship with the ‘porches’ and ‘towers’ of the presidential administration. On one of them, Rodina is linked to Vladislav Surkov, the deputy head of the presidential administration. 21

Vladislav Surkov’s influence on Rodina was mentioned even by Glazyev during his conflict with Rogozin in February-March 2004. At the time he cautioned that if the ‘Surkov-Rogozin’ group should win, the fraction would ‘no longer represent the interests of the people who voted for it, but will simply become a branch of the presidential administration’. ‘I don’t want to take part in a squabble with Glazyev, but I won’t let the Rodina fraction be turned into a centre of anti-Putin forces either,’ Rogozin replied then. 22

Andrei Saveliev, ‘On Glazyev, Rodina and political shamelessness’ (February 2004) 23:

‘A myth is being spread that Rogozin is fulfilling the Kremlin’s directive to control Glazyev. Common people get the impression that the cynical and robust guy Rogozin is hurting little honest boy Seryozha. In fact the situation is totally different. It is Glazyev who is executing the order of one of the Kremlin’s “towers”

– those people who intend to transform Glazyev and the Rodina bloc into puppets that can be used to blackmail the President or, should the situation change, provide loyal services to him.’

On the other account, Rodina is linked to the so-called ‘Petersburg siloviki24’ (or ‘Petersburg Chekists’) led by Igor Sechin (deputy head of the presidential administration).

The link between Sechin and Rogozin was publicly discussed in the autumn of 2003: several newspapers (among others, Sovetskaia Rossiia, the main paper of the Communist Party) published a transcript of a telephone conversation between ‘Dima’ and ‘Igor Ivanovich’ dated autumn 2003, containing extremely rude comments on Sergei Glazyev and his political prospects. Rogozin flatly denied that such a conversation had taken place, though he did not deny that he had consulted with Igor Sechin over the telephone: ‘I know for sure that this conversation never took place’, ‘I did not discuss Glazyev with Sechin’, ‘of course there is no tape, probably there are transcripts of actual tapped conversations’. (On-line press conference on the Utro.ru web site, 5 February 2004)

Here is the beginning of the published transcript:

‘- Dima, hi!.

- Hello, Igor Ivanovich. May you be healthy.

-Come on, don’t be bowing and scraping too much. You’re a good boy as it is. You’re doing everything as you should.’ 25

In more sophisticated explanations, Rodina’s fate is described as a resultant of the influence of two (or more) groups in the presidential administration. On these accounts, for example, there were two competing projects during the 2003 Duma elections. For the ‘Surkov project’ it would have been enough for Rodina to garner just under 5% of the vote, taking as many votes as possible from the Communist Party but staying out of the Duma. The ‘Petersburg siloviki’, on the other hand, needed Rodina as a nationalistic and pro-statist party in the Duma. This was how things looked to the head of the Politika Foundation, Vyacheslav Nikonov (the grandson of Stalin’s prime minister, Vyacheslav Molotov), 26 the Gorbachev Foundation analyst Valeri Solovey27 and others. The ensuing dramatic turns in Rodina’s career, such as the departure of Baburin’s supporters in the summer of 2005, are explained in a similar way – as a ‘struggle between the towers [of Kremlin]’. This explanation was advanced especially by Tatiana Stanovaia, the director of the analytical department of the Centre for Political Technologies28 and the left-wing socialist Boris Kagarlitsky. 29

‘Nationalists’

Accusations of radical nationalism. xenophobia and anti-Semitism are the most common criticisms levelled against Rodina.

The pitch for this criticism was set in December 2003 – in the final days before the Duma elections. Politicians from the Union of Right Forces (SPS) made a series of harsh statements to the effect that the Rodina bloc represented a threat of ‘national socialism’ (alluding to the German Nazi Party), being simultaneously socialist and nationalist.

‘National socialism is mould. And mould needs to be destroyed!’, SPS leader Anatoli Chubais said immediately after the elections, promising to ‘purge the Duma of the brown mould’30 .

A year later, the leader of the ruling United Russia party, Boris Gryzlov, in a speech at the party congress in November 2004 offered a new definition – ‘cave-age nationalism’. According to Gryzlov, Rodina’s leader sometimes ‘doesn’t think it beneath him to appeal to the basest human feelings, such as a cave-age nationalism that is unacceptable in the modern world’. ‘It is better to be a cave-age nationalist than a cave bear’, Dmitri Rogozin replied, alluding to United Russia’s universally known party symbol, the brown bear. 31

The following year, especially during the Moscow elections, the accusations became even harsher. Moscow’s Mayor Yuri Luzhkov, speaking on the Moscow city TV channel TVTs on 15 November 2005, called Rodina a ‘black-hundred-type party’32; the chairman of the Moscow City Duma, Vladimir Platonov, commenting on the court ruling to take Rodina off the elections, remarked with satisfaction:

‘64 years later, the fascists have once again been stopped in Moscow. […] We can be proud of that.’ 33

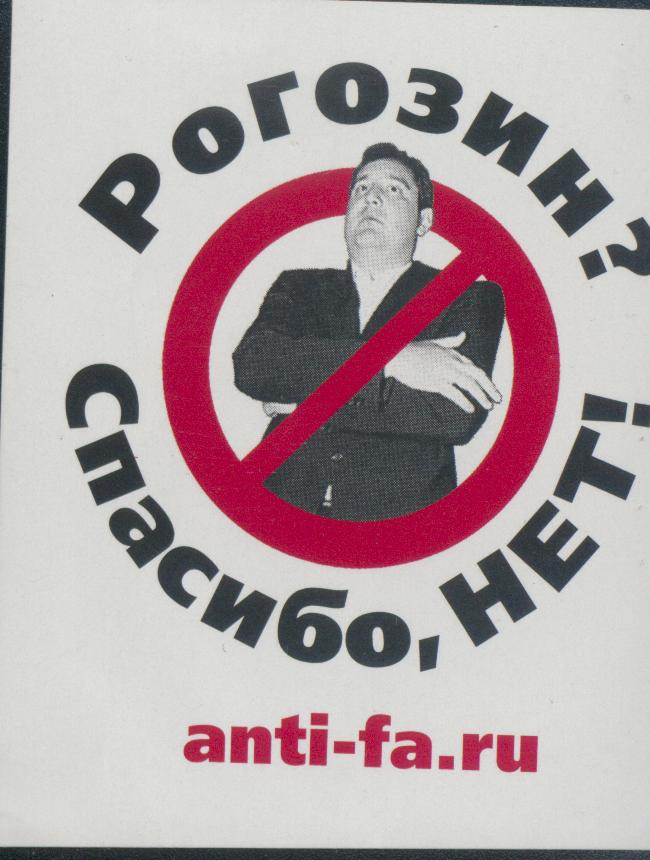

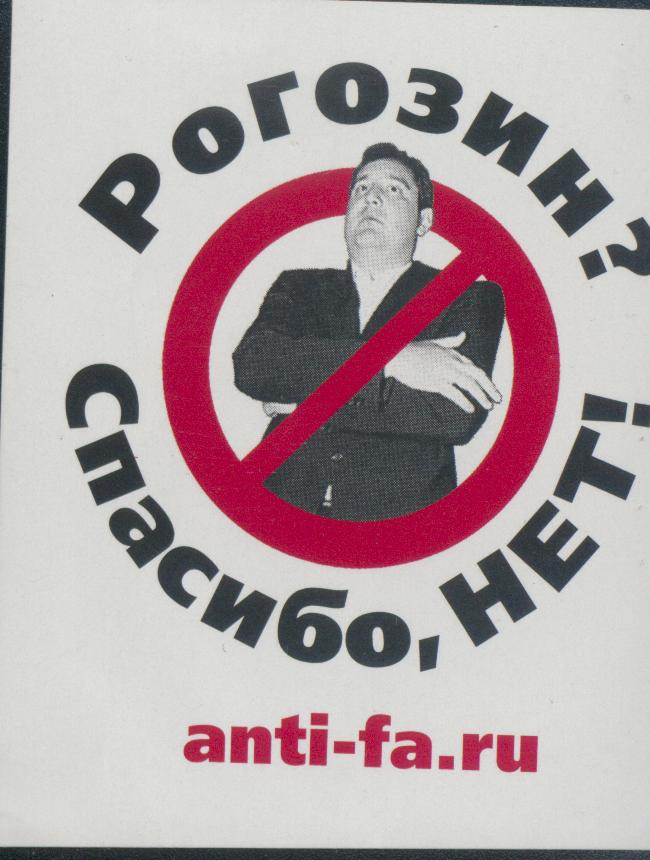

Anti-fa. ‘Rogozin? No, thanks!’ sticker (2005)

|

The ‘anti-fascist pact’ that was signed by twelwe parties in February 2006 at United Russia’s initiative, says:

‘Today, unfortunately, certain political parties and social organisations openly co-operate with advocates of a nationalist ideology, providing these modern fascists with a parliamentary platform, newspaper space and airtime, thereby turning them into respectable politicians and legalising an inhuman philosophy’.

In their written and oral statements, United Russia members make it clear that by ‘certain parties’ they mean above all Rodina.

Rodina has taken different stances towards these charges. Rogozin usually laughs off the early accusations of national socialism: ‘All these stupid formulas of Chubais’s about me being a nationalist, Glazyev a socialist, and the two of us taken together, national socialists, are simply an indication of Chubais’s ignorance. It’s like the guinea-pig that’s actually neither a guinea nor a pig.’ 34

In response to Boris Gryzlov’s charges of ‘national populism’ and ‘cave-age nationalism’, deputies from the Rodina fraction issued a statement which said that ‘during the election campaign the Rodina (People’s Patriotic Union) bloc didn’t conceal its views and intentions from anyone’ and reproached Gryzlov for not once using the word ‘Russian’ in his speech.

Finally, Rodina members react highly sensitively to accusations of nazism or fascism. People who use these terms to describe the party must be prepared to face slander suits. Rodina party activists have, for example, sued Ella Pamfilova, the leader of the Russian president’s civil society development and human rights council. Appearing on television (on the Vesti-plyus programme) in October 2005, Pamfilova said that, according to information available to her, many members of Rodina ‘are also sick with, let us say, I wouldn’t say nationalism, because a healthy nationalism is typical of every normal people, but I would say nazism...’. As this brochure was being written, the court had not yet decided on this case.

About half a year before the 2003 elections, the future Duma deputy Andrei Saveliev, one of the main instigators of the legal suits against Ella Pamfilova, wrote an article which was indeed highly critical of nazism and Hitlerism. According to Saveliev, it is in Italian fascism, rather than German nazism, that one must look for positive experience:

‘…fascism gave expression to certain traits of the general aspirations of the nation and the national spirit which are impossible to extirpate’; fascism ‘is modern in its state-building pathos and its technology of social progress’; ‘clarify the differences with fascism, but at the same time take certain clear formulations from it’ which may be ‘highly influential and promising for the purposes of state- and nation-building’.35

When necessary, Rodina is prepared to make statements condemning xenophobia, racism, chauvinism and religious intolerance. Such a statement was adopted, for example, at a meeting of the party’s political council in February 2006. Rodina members are prepared to argue that these definitions do not apply to them.

Both critics and supporters are indeed finding it difficult to find a proper definition of Rodina’s political position. The party, at its congress in June 2004, called itself ‘social-patriotic’, but this definition hasn’t caught on so far.

The main reason for these difficulties is that Rodina, both as a party and as a fraction, remains highly heterogeneous. One and the same party includes, on the one hand, Oleg Shein, a left-wing workers’ leader whose views are close to those of the Fourth International, and the miners’ union leader Ruben Badalov, and on the other hand the deputies Alexander Chuev, Alexander Krutov and Natalia Narochnitskaia – religious fundamentalists who, in terms of style and attitudes, are close to American pro-life and creationist activists. Rodina’s fraction also includes, for example, two representatives of the People’s Patriotic Party (Narodno-patrioticheskaia partiya) created in 2002 – the party’s leader, former defence minister Igor Rodionov, and his deputy, Oleg Mashchenko. One of the main programmatic aims of the party is to ‘throw off the Masonic-Zionist, liberal-democratic yoke’. 36

It is difficult for a heterogeneous party to survive and preserve its unity; but there is also a greater likelihood that, in a changing political environment, one of its parts will be successful. The two leaders of the Rodina bloc, Dmitri Rogozin and Sergei Glazyev, still have some political prospects. Be it jointly or apart, with Rodina or under another party’s flag, they can hope to soar to new political heights as they did in 2003.

If we want to define Rodina by comparison, we should turn to two political scenes: in Europe, the closest similarities are with the ‘new wave’ of right-wing radicals – politicians who are about as concerned about the inflow of immigrants and determined to ‘preserve the nation’ as Rodina is: Jean-Marie Le Pen (2002), the late Pim Fortuyn (2002) and Jörg Haider (1999–2002). In Latin America, there are parallels with left-wing populists, such as Hugo Chávez in Venezuela and Evo Morales in Bolivia, who are speaking out against foreign capital and for the nationalisation of ‘strategic’ branches of the economy. These parallels are probably not accidental. Russia indeed resembles the old European countries in the sense of being unexpectedly confronted with the problem of preserving its cultural identity and socio-eco-nomic stability. And Russia bears a resemblance to Latin American countries that are heavily involved in economic exchanges with the main centres of the world economy (above all Europe and North America) without having the economic strength to face her partners on equal terms. Taken together, these circumstances will continue to affect Russian political life. The favourable economic conditions of recent years which have toned down these problems will one day cease to exist, and then the challenge of national populism may put Russia to a serious test.

Scenes from the Life of Rodina

The ‘Letter of the 500’

On 13 January, 2005, approximately 20 State Duma deputies submitted a request to the Prosecutor-General’s Office to initiate official legal proceedings to prohibit all Jewish religious and ethnic associations in Russia for extremism.

The list of deputies who signed the appeal was published in the Izvestiia newspaper (25 January 2005): Sergei Glotov, Anatoly Greshnevikov, Sergei Grigoriev, Alexander Krutov, Nikolai Leonov, Oleg Mashchenko, Vladimir Nikitin, Nikolai Pavlov, Igor Rodionov, Andrei Saveliev, Yuri Saveliev, Irina Savelieva, Ivan Kharchenko, Aleander Chuev (all from the Rodina fraction; Glotov, Greshnevikov and Savelieva later joined Sergei Baburin’s ‘Rodina-2’); Nikolai Yezersky, Vladimir Kashin, Nikolai Kondratenko, Albert Makashov, Piotr Svechnikov, Sergei Sobko (all from the CPRF fraction). The deputy Alexander Chuev (a non-anti-Semitic ultra-conservative fundamentalist) immediately denied having signed the appeal.

The appeal triggered an unprecedented scandal that lasted about a month. The deputies withdrew the appeal from the Prosecutor-General’s Office on 25 January ‘for technical changes’ and didn’t hand it in again, but by that time the debate had gained momentum against the background of Vladimir Putin’s visit to the former Auschwitz concentration camp to commemorate the 60th anniversary of its liberation.

On 4 and 9 February, respectively, the State Duma and the Federation Council – the lower and upper houses of parliament – adopted resolutions condemning anti-Semitism. The deputies who had supported the appeal were invited to TV talk shows: general Albert Makashov (CPRF) was featured in the NTV show ‘Duel’, and Sergei Sobko (CPRF) and the TV journalist Alexander Krutov (Rodina) in the First Channel’s ‘Times’.

The appeal written ‘in connection with the increased use against patriots of art. 282 of the Penal Code of the Russian Federation for “incitement of ethnic strife” against Jews’ starts by quoting the statistical data that Vladimir Putin mentioned in December 2003: in 1999, four people were sentenced in accordance with article 282 of the Penal Code of the Russian Federation which outlaws ‘incitement of inter-ethnic strife’, ten people were sentenced in 2000, and in 2003, ‘over 60 cases were opened, about 20 were brought before a judge. And there were about 17–20 convictions’.

Thus, the appeal asks:

‘We admit that statements by Russian patriots about Jews are often sharply negative, excessively emotional, and unacceptable for public discussions, and this is interpreted by the courts as extremism. However, at the above-mentioned trials, there has never been an investigation of the reasons for such sharp hostility and for the primary source of such extremism in this interethnic conflict.

Indeed, the main point that investigators and courts must establish is the following: do the negative statements about Jewry by Russian patriots correspond to the truth of the issues they refer to? If there is no truth to them, then yes, one can say that the Jews are being humiliated and that there is incitement of religious and ethnic strife. If there is truth to them, however, then such statements are justified and, regardless of their emotional nature, they cannot be considered as humiliating, inciting (ethnic) strife etc. (For instance, calling a decent person a criminal is humiliating for that person; but calling a convicted felon a criminal is a true statement of fact.)

Moreover, since in the inter-ethnic conflict at hand there are two parties (the accusers and the accused), it must be establish which side started the conflict and is responsible for it, and whether it is possible that the actions of the accused are a self-defense against the aggressive acts of the accusing party.’

And the appeal immediately goes on to answer this question:

‘We make free to assure you, Mr Prosecutor-General, that, concerning this issue, there exists throughout the whole world a large amount of widely recognised facts and sources, on the basis of which the following conclusion can be drawn: the negative statements by Russian patriots about typical Jewish acts against nonJews are based on truth. Furthermore, these acts do not happen by chance, but are prescribed by Judaism and have been practiced for two thousand years. Consequently, statements and publications against the Jews attributed to patriots in the majority of cases constitute self-defense which may not always be stylistically appropriate, but is justified in its essence.’

‘Law enforcement agencies should, in accordance with article 282 of the Russian Federation’s Penal Code, curtail the proliferation of a religion that incites hatred among Jewry towards the rest of the “population of Russia”.’

The main argument in favour of prohibiting all Jewish organisations is based on quotes from the book Kitzur Shulkhan Arukh, supplemented with statements by contemporary Jews – politicians, journalists and businessmen. The appeal then draws the following conclusion:

‘It can be said that the entire democratic world today finds itself under the financial and political control of international Jewry, which is a subject of unconcealed pride for some influential bankers (J. Attali and others). And we don’t want to see our Russia, against whose rebirth an ongoing permanent preventive war without rules is being waged, among these unfree nations. This is why, in the interests of both the defence of our Fatherland and personal self-defence, we are obliged to appeal to you, Mr Prosecutor-General, with an urgent request to examine the above-mentioned outrageous facts at the earliest possible date and, should they be confirmed, in accordance with the appropriate articles of the Penal Code of the Russian Federation, the law “On Countering Extremist Activities” (2002) and art. 13 of the Russian Federation’s Constitution (“The establishment and the activities of public associations whose aims and actions are directed at […] the incitement of social, racial, national and religious strife shall be prohibited.”) officially to instigate proceedings to prohibit all Jewish religious and national organisations for extremism.’

The appeal was written by the writer Mikhail Nazarov, formerly a non-returnee dissident who worked at the Posev journal in Germany, and more recently the editor of the Russian Idea book series. In 2002, Nazarov bought a copy of the Kitzur Shulkhan Arukh and was so impressed that he immediately wrote a brochure entitled The Law on Extremism and the Shulkhan Arukh (published by the Zavtra newspaper in a shortened version entitled ‘Fascism in Kitzur Shulkhan Arukh’).

Mikhail Nazarov’s brochure came in useful in November 2004, when a social movement called ‘Living without Fear of the Jews!’ (Zhit bez strakha iudeiska!, LWFJ) was created at a mass-meeting in support of Boris Mironov, who had been Press Minister in the mid–1990s and was wanted on a federal warrant on charges of inciting inter-ethnic strife.

The LWFJ activists model their activities on the famous ‘Beilis affair’37 of 1911–13. They collected signatures for the appeal, claiming to have 500 in January, 5,000 in March (when the appeal was resubmitted to the Prosecutor-General’s Office), and 15,000 in July-August 2005. At the end of 2005, the Union of the Russian People (Soiuz russkogo naroda, named thus in honour of the best-known right-wing nationalist organisation of the early 20th century), created in November 2005 and led by the sculptor Viacheslav Klykov, joined the campaign. At the founding convention of the Union of the Russian People (in November 2004), Sergei Baburin and Sergei Glazyev (who are now, respectively, co-chairmen of the two competing Rodina fractions in the State Duma) gave complimentary addresses.

The ‘Let Us Purge Moscow!’ TV spot

The ‘Let Us Purge Moscow!’ TV spot, which was broadcast on the Moscow-based TV station TVTs in early November 2005, was the most notable event in the Moscow elections and probably one of the most remarkable political events of the year. By releasing this spot, Rodina came to be discussed by almost every politician and commentator, but it paid a high price. The party was taken off the city elections, and consolidated its reputation as a collection of ‘xenophobes’ and ‘extremists’.

Here is the content of the spot:

Caucasian music is playing. Several Caucasians are sitting on a bench in a courtyard eating watermelon; pieces of watermelon skin are scattered around them. A blonde, Slavic-looking woman is walking past them with a pram. There is a close-up of the pram wheels running over the pieces of skin. ‘They’re coming in swarms!’ grumbles one of the Caucasians, the other keeps littering the ground with watermelon skin. Suddenly, Rogozin and Popov38 appear, wearing raincoats.

Rogozin (sternly): Pick this up. Clear this away.

Popov (grabbing one of the Caucasians by the shoulder):

Do you understand Russian?

An off-screen voice: ‘Let us purge our city!’

Caption: Rodina political party. Let us purge Moscow of rubbish!

Rodina’s PR people were inspired by the disorders in the Paris suburbs, which also took place in November 2005, to create another version of the same spot. The ‘French’ version of the spot starts with a view of the Eiffel tower and the caption ‘Paris, a year ago’, followed by the same scene as in the other spot, only with French dialogue. The French embassy in Moscow wasn’t amused by this modification. The embassy ‘expressed regret’ at the spot which ‘exploited the recent events in an inappropriate way’ that ‘distorts the actual events in France’ and ‘doesn’t correspond to the spirit of understanding which exists in Franco-Russian relations’.

In the course of November, while Rodina was still running in the elections and the stir created by its spots was increasing by the day, Dmitri Rogozin and other party activists made it clear that they were pleased with the impression they had made and that their provocation (in a good sense) had attracted attention to the party and the issues it raised.

‘We are talking about the cleanness of the city, about the cleanness of the soul, about the fact that one shouldn’t leave litter about, and we want people not to behave boorishly – those who have been living in the city for a long time as well as those arriving here should behave decently.’

Dmitri Rogozin at a press conference at the Interfax press agency, 16 November 2005

The question ‘Do you understand Russian?’ is entirely neutral and carries no more offence than ‘Do you speak English?’, explained the chairman of Rodina’s fraction in the Moscow State Duma, Viktor Volkov.

Sergei Butin, the head of the Rodina fraction’s press service, was also trying hard to argue that the spot ‘doesn’t touch upon the ethnic question’ and that the bad guys scattering rubbish ‘are people without ethnicity’:

‘I could even imagine that the ruffians in this spot were played by Jews rather than Caucasians. Or perhaps simply swarthy Russians. In fact, Rogozin himself resembles a Caucasian person more than all those ruffians portrayed there.’

National News Agency (annews.ru), 13 November 2005

Andrei Saveliev, a member of Rodina’s political council and Rogozin’s long-standing companion-in-arms, proposed an even bolder interpretation: the spot was conceived as a ‘lithmus test’ to reveal closet racists.

‘I believe this spot has very clearly revealed who is a racist in our society. Those who, at a quick glance, determined that the people portrayed in the spot were Caucasians; those who think that people, rather than watermelon skins, are street rubbish – those are the blunt racists. Thus one of the indirect aims of this spot was precisely to expose such characters.’

Utro.ru, 8 November 2005

As a result, Saveliev argued, ‘the liberal racists took the bait which Rodina had prepared specially for them’ – the plan had worked.